December 22, 2025

When the Site Looks Finished Before It Behaves That Way

On many sites, erosion control appears finished long before the work actually is. The ground is covered, erosion control products are in place, inspections pass, and crews move on. For a moment, everything appears stable enough to keep the schedule intact.

Then conditions shift. Not dramatically, and not all at once. A storm passes through. Access points soften. Sediment moves where it hadn’t before. Nothing that reads as a failure in isolation—just enough to require attention again.

So crews return. Areas are touched up. Materials are reset. The site becomes workable once more. This cycle repeats quietly across projects, not as a missed deadline but as a series of small interruptions that accumulate over time.

What makes this difficult to notice is that nothing seems obviously wrong. The measures in place often do what they were meant to do in the moment. The cost shows up later, in how often progress has to circle back—time spent again and again, in increments small enough to feel routine.

Why Topsoil Loss Is Treated as a Short-Term Cost

Globally, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that approximately 33% of the world’s soils are already moderately to highly degraded due to erosion, compaction, and loss of organic matter, reducing their ability to regulate water and remain structurally stable.

What slows projects over time is not erosion itself, but how its cost is framed. Topsoil loss is treated as a surface condition to be corrected after it appears, rather than a finite resource whose removal quietly compounds risk. Once that framing takes hold, replenishment becomes a downstream task—something to patch, replace, or buy back when necessary.

That approach carries assumptions that rarely hold up. Topsoil forms slowly, often over centuries, while replacement happens quickly and at increasing expense.

Soil science literature notes that forming just 2–3 cm of topsoil can take up to 1,000 years under natural conditions, depending on climate, parent material, and biological activity.

As fertile material becomes harder to source in many regions, the cost of purchasing, transporting, and reapplying it continues to rise. Still, those future costs tend to be discounted, while upfront investment in preservation is seen as friction. Compliance gets prioritized because it is immediate and visible; preservation gets deferred because its value unfolds over time.

How Projects End Up Solving the Same Problem Repeatedly

The pattern begins well before any material is installed. It starts with how projects are structured and evaluated. Work is broken into phases, each with its own handoff, inspection, and definition of completion. Erosion control often sits at the boundary between those phases—important enough to be checked but rarely integrated into how the site is expected to behave weeks or months later. Success is measured at the moment of inspection, not across the sequence of conditions that follow.

That framing shapes decisions on the ground. When schedules are tight and scopes are segmented, surface coverage becomes the fastest visible signal of progress. A treated slope, a covered haul road, and a stabilized pad—each looks complete enough to move forward. The system rewards that appearance because it allows the next activity to begin. What happens after that moment is harder to assign, harder to track, and easier to defer.

So erosion control becomes reactive by design. Loss is addressed after it occurs. Topsoil is replaced after it moves. Sediment is cleaned up after it settles where it shouldn’t. These responses feel practical because they fit within familiar workflows. Material can be sourced, delivered, and placed. The site returns to a workable state. On paper, the issue is resolved.

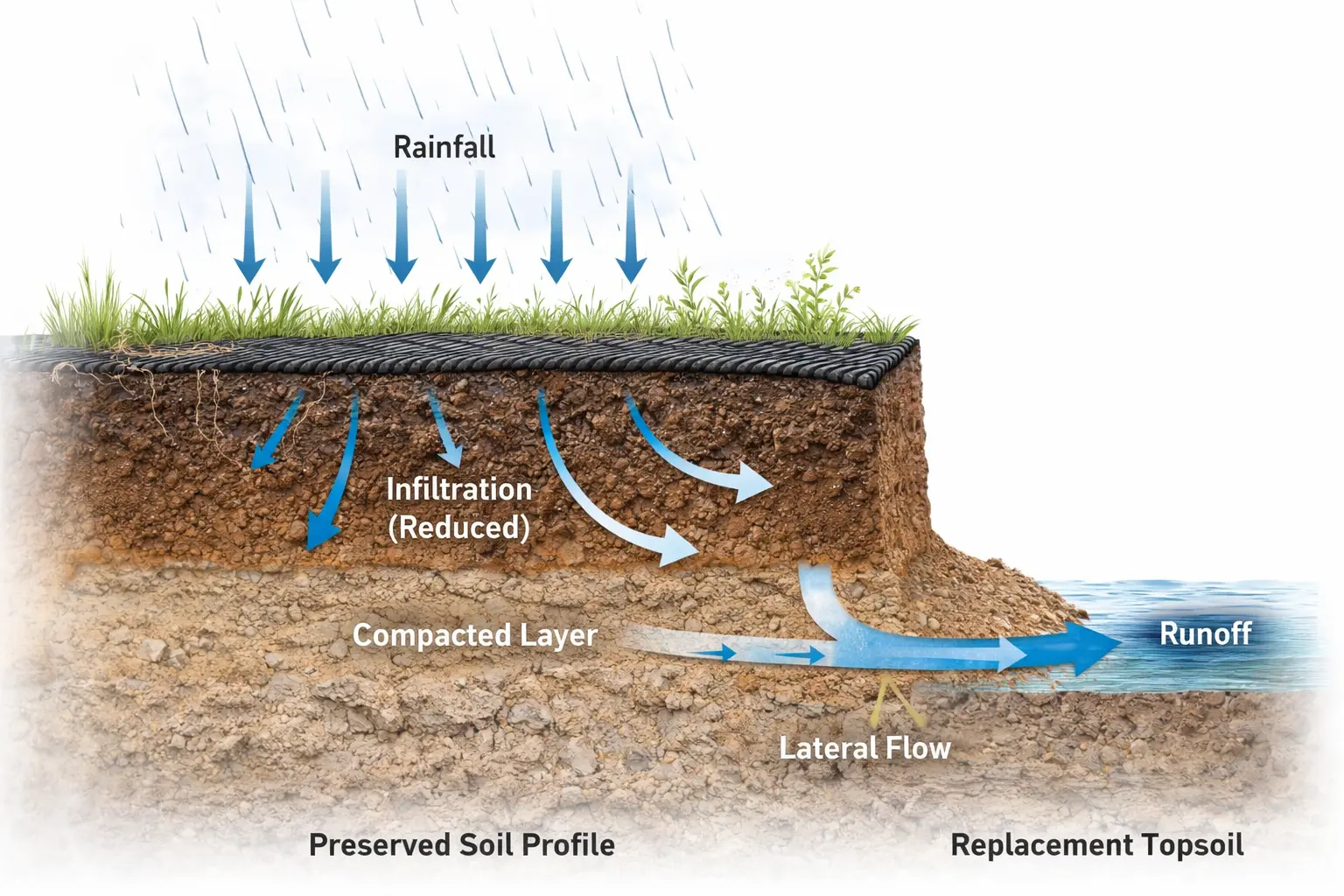

What gets missed is how the ground itself changes with each cycle. When topsoil is disturbed or lost, the soil structure beneath it is often compacted, stripped of organic matter, or left with reduced infiltration capacity. Experimental studies show that repeated wet–dry cycles reduce soil aggregate stability and shear strength, increasing runoff and sediment loss even when rainfall intensity remains similar across events.

In the first storm, the surface may hold. In the second or third, runoff accelerates. In compacted or structurally degraded soils, water tends to move laterally instead of infiltrating downward. Areas that were once stable begin to shed material more easily, even under similar rainfall.

This is why repetition often matters as much as single severe events, particularly when soil structure is progressively weakened. Many sites do not fail because of a single extreme event. They degrade through a series of ordinary ones. Each wet–dry cycle weakens soil cohesion. Each replacement layer lacks the biological structure that took far longer to form. The ground becomes more dependent on surface-only erosion control products to remain workable, not less.

At the same time, replacement becomes more costly. Topsoil is not a uniform commodity. Its availability depends on location, land use, and competing demand. As development expands and fertile land is converted, sourcing suitable material becomes more expensive and more logistically complex. Transport distances increase. Handling and placement add labor. Yet these costs often appear later in the project timeline, disconnected from the decisions that made them necessary.

This delay reinforces short-term thinking. Upfront preservation can look like an added expense because its benefits are not immediately visible. Replacement feels easier to justify because it solves a present problem with a familiar transaction. Compliance aligns with this logic. It provides a clear threshold—installed or not, present or missing—while long-term performance remains diffuse and harder to attribute.

Over time, these dynamics converge. Sites stabilized quickly but superficially require more frequent attention. Crews return not because controls were absent, but because the ground no longer behaves predictably between visits. Each return feels minor. Each adjustment seems reasonable. Together, they create drag—lost hours, disrupted sequencing, and administrative effort that accumulates quietly.

This is the paradox at the center of surface-only fixes. Measures chosen to reduce immediate risk can increase long-term dependence. The more often soil is replaced rather than preserved, the more fragile it becomes. And the more fragile it becomes, the more effort is required to keep work moving.

Nothing in this process is irrational. The choices make sense within the system that produces them. The cost only becomes clear when those choices are viewed not as isolated responses, but as part of a longer chain—one where time, soil, and repetition interact.

Redefining Progress on Ground That Changes Over Time

Moving forward does not begin with choosing a different product or method. It begins with changing what “progress” is taken to mean. On unstable ground, progress is not the moment a surface looks complete. It is the point at which the site continues to behave as expected between visits, storms, and phases. In that frame, speed becomes a property of continuity, not installation.

Projects that hold this perspective tend to make different trade-offs, often without announcing them as such. They treat erosion control as something that unfolds over time rather than something that gets checked off. Instead of asking whether a measure is present, they pay attention to how the ground responds after it has been stressed. The second storm matters more than the first. So does what happens when crews are no longer nearby to reset conditions.

This shift shows up in how soil is regarded. Where surface-only approaches assume the ground beneath will remain passive, more resilient projects assume the opposite—that soil will change, weaken, and respond to disturbance unless it is actively supported. Effort is spent earlier on preserving structure, infiltration, and cohesion, not because it looks better on day one, but because it reduces how often the site demands attention later.

It also changes how temporary measures are evaluated. Fast-acting treatments—including erosion control polymers in specific contexts—still have a role, particularly where access needs to be maintained or dust must be controlled immediately. The difference lies in whether those measures are expected to carry the full burden of stability or whether they are understood as part of a broader sequence that includes recovery and reinforcement of the soil itself. In the latter case, short-term tools buy time without quietly increasing dependence.

Perhaps the most important change is how cost is interpreted. Initial investment in preservation often appears as friction because its payoff is diffuse. Fewer return visits. Fewer resets. Fewer small delays that never show up as a single failure. Over time, those avoided interruptions begin to outweigh the visible savings of surface-first fixes, even if they are harder to attribute to any one decision.

Seen this way, erosion control is less about preventing loss in isolated moments and more about maintaining predictability. A site that behaves consistently allows work to proceed without constant recalibration. That steadiness is what keeps schedules intact—not the absence of erosion entirely, but the absence of surprise.

At its core, this is not a technical adjustment. It is a shift in responsibility across time. When soil is treated as something to be replaced after it moves, instability becomes routine. When it is treated as something to be preserved before it degrades, continuity becomes possible. The difference is subtle in the short term. Over the life of a project, it is decisive.

What Becomes Visible When Time Is Allowed to Matter

Over time, the difference between fast work and lasting work becomes harder to ignore. Not because something fails outright, but because the ground keeps asking to be revisited. Small returns accumulate. Adjustments become routine. Progress continues, but it does so unevenly, shaped as much by recovery as by forward motion.

This is rarely framed as a choice. It emerges from how success is defined in the moment. When stability is judged by appearance, surface conditions carry more weight than underlying behavior. When time is measured in phases rather than sequences, the future is discounted by default. Nothing about this is careless. It is simply how systems behave when immediacy is rewarded more clearly than endurance.

Topsoil makes this visible because it cannot be hurried back into place once it is gone. Its loss exposes the difference between correction and preservation, between reacting to change and accounting for it. What looks efficient in isolation can become fragile when repeated often enough.

In the end, the issue is not erosion alone. It is how projects account for what compounds quietly. Speed, when understood only at the surface, tends to spend itself quickly. When understood across time, it begins to hold.

That distinction is subtle. It is also where durability begins.

Applications - Dust Control & Soil Stabilization Products

Leave a Reply