October 28, 2025

The Cycle We’ve Stopped Paying Attention To

Every dry season begins the same way. Graders carve the surface, water trucks follow, and for a few quiet hours, the dust disappears. Then the heat returns, the fines lift, and the haze settles back over the road. The routine feels responsible—visible action against a visible problem—but it’s a loop that never ends.

Across construction sites, mining haul roads, and county corridors, this pattern repeats. Schedules tighten, costs rise, and the surface still degrades under the same traffic. Each watering round buys a few hours of control at the price of another day’s labor, fuel, and water. What seems like maintenance is really repetition disguised as progress.

Behind those drifting clouds lies more than inconvenience. Road dust reduces visibility, accelerates wear on equipment, and sends fine particulate matter—PM10 and PM2.5—into the air that regulators and communities now watch closely under EPA particulate matter standards and guidance. Road dust reduces visibility, accelerates wear on equipment, and releases fine particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) into the air, a pattern long detailed in EPA field data for unpaved roads. Yet because the work is familiar, it rarely gets questioned. The grader moves, the truck sprays, the budget renews—and the system keeps itself busy.

It’s easy to see dust control as a chore. Harder to see it as infrastructure quietly eroding from neglect. But that’s where the contradiction lives: what we treat as routine upkeep might actually belong to the foundation of the road itself.

From Compliance to Continuity

In many regulated operations, especially construction and mining, dust control is documented through watering logs and dust control plans to prove compliance with PM10 and opacity limits to inspectors, and those records often become the main evidence that an operator is ‘in control.’

But paperwork is not performance. When dust control products exist only to satisfy oversight, they drift away from the purpose that created them—to protect people, air, and ground alike. The result is effort without endurance: the surface looks managed, yet the cycle of erosion, regrading, and re-spending continues.

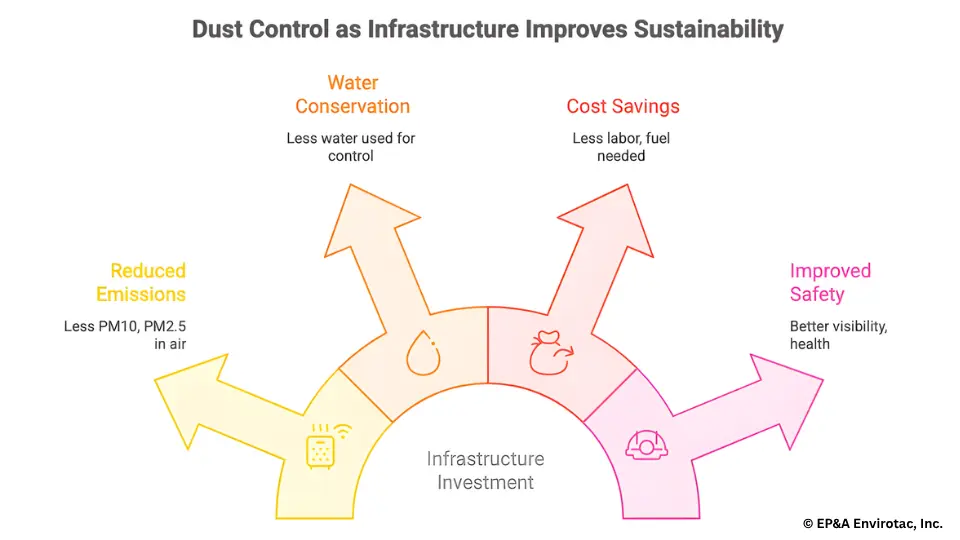

True stewardship begins when dust control is treated as part of the infrastructure itself—planned, budgeted, and measured for continuity rather than compliance. Because dust doesn’t only affect a road; it travels through the air workers breathe, the crops nearby, the engines downstream, and the communities that live beside the route. Seen from that wider frame, road dust management isn’t an expense to justify; it’s a foundation to sustain.

The System Beneath the Surface

The persistence of the “maintenance mindset” isn’t born of negligence; it’s built into the way infrastructure is funded and measured. Budgets favor what can be seen, quantified, or ribbon-cut. Pavement, bridges, culverts—these belong to capital plans. Dust control lives somewhere between a fuel receipt and a safety note, financed from operating budgets that reset every fiscal year. When the ledger treats a road’s surface as expendable, management does that too.

Compliance culture reinforces the cycle. Reporting frameworks reward demonstration, not duration: a completed watering log satisfies oversight, even if the surface unravels by afternoon. The visual cue—a damp road, a passing truck—becomes proof of diligence. But diligence is not durability. Each compliance round consumes more water, more fuel, and more labor while postponing the structural fix that would make the need smaller next season.

There’s also a psychology at work. Success in dust control is quiet; failure is loud. A clean, clear horizon earns no credit, while a single afternoon plume prompts community complaints and regulatory scrutiny. Over time, organizations learn to manage perception instead of condition. They chase visible calm instead of structural continuity.

Yet compliance itself isn’t the villain. Oversight protects air, workers, and nearby communities. The issue lies in scope: compliance asks whether control occurred, not how it endures. The broader lens, what might be called a 360° view, includes the health of operators breathing the air, residents downwind, machinery exposed to abrasion, and the watershed absorbing runoff. Within that system, dust isn’t just a maintenance by-product; it’s a signal of infrastructure failing to hold its boundaries.

When viewed through an accounting lens, the pattern compounds itself. Each round of watering and regrading is booked as a routine expense—small, familiar, and easily approved. But multiplied across fleets, seasons, and years, those small costs accumulate into a quiet form of capital erosion. The surface, the equipment, and the budget all degrade together. Reframing dust control infrastructure isn’t about spending more; it’s about classifying the spend correctly—shifting polymer-based dust control systems and sustainable surface stabilization treatments from OPEX to CAPEX within asset management plans. A single, planned investment in surface integrity can often displace years of reactionary work. The economics simply reveal what the system already knows: maintenance without continuity is debt by another name.

Designing for Continuity

Reframing dust control as infrastructure begins with how it’s planned. Maintenance thinks in shifts; infrastructure thinks in seasons. The shift-based mindset measures success in the hours after application. The seasonal mindset measures how the surface performs through change—heat, traffic, and weather cycles. The difference isn’t in material, but in horizon.

The first practice is planning for continuity rather than reaction. Instead of authorizing watering whenever dust becomes visible, agencies can map renewal windows the way they plan seal-coating or drainage maintenance—anchored to weather patterns and use intensity. A scheduled, preventive cadence converts scattered expenses into a predictable program, allowing performance data to inform the next cycle.

The second practice is to treat the system as the decision-maker. Climate, soil gradation, and traffic class define a surface long before any suppressant is applied. Matching method to environment—chlorides can be effective in dry regimes, while lignin or other bio-based blends are used on forest and low-volume corridors. Engineered acrylic polymer emulsions are applied where higher cohesion or endurance is required, turning dust control into an environmental design rather than a procurement approach. For clarity in this article, “dust control polymers” refers to polymer emulsions—here, acrylic ones that bind fines and form a durable surface film. In some programs, natural stabilizers such as hydroseeding, straw mulch, or compost binders extend that design by anchoring the surface biologically, letting vegetation and material science work in tandem. Each approach has its place when chosen for compatibility, not convenience. Yet methods that depend on constant reapplication or contribute to runoff and corrosion reveal how maintenance thinking still dominates policy.

Next comes measuring what matters to both operators and oversight. Measuring how many gallons are sprayed tells you how busy the trucks were, not how stable the road is. More revealing indicators include the number of watering events avoided over a season, the consistency of traction after storms, or the reduction in visible plumes at operating speed. None require lab equipment—only observation recorded with discipline. When those records show endurance instead of activity, the budget conversation changes on its own.

A complementary practice is integrating dust control into infrastructure asset-management plans. Unpaved and haul roads can be logged like bridges or drainage systems, with attributes—surface type, binder class, treatment date, and performance notes. This simple database converts anecdote into asset history, making renewal funding defensible within capital planning frameworks. It also allows cost-per-kilometer-per-season comparisons that expose the hidden expense of short-term cycles.

Water stewardship follows naturally. Every truckload saved is both a budget and an environmental gain. Tracking fuel and water consumption against treated versus untreated segments often reveals efficiencies that outweigh material costs. In many regions, regulators already count water use toward sustainability reporting; connecting those dots turns dust control programs into climate-adaptation evidence. It also aligns with environmental compliance standards for particulate matter reduction and air-quality management.

Safety and compliance evolve in parallel. When stabilized surfaces hold cohesion longer, visibility improves, PM10 particulate emissions decrease, and occupational-health metrics improve. Those are the same outcomes environmental auditors monitor. Embedding dust-control performance into safety KPIs closes the loop between compliance paperwork and real-world results.

There’s also a cultural practice: treating surface integrity as shared responsibility. Mechanics, operators, and environmental staff often work in separate lanes; dust brings their interests together. Cross-training crews to observe surface condition, track watering frequency, or report early degradation turns daily work into system feedback. What was once “extra duty” becomes part of operational literacy.

Finally, budget reclassification anchors the shift. Some agencies already move durable surface treatments—including polymer-stabilized or vegetatively anchored segments—from operating to capital accounts when they extend asset life beyond a fiscal year. It’s an accounting change that signals intent: this isn’t upkeep; it’s preservation. Framed that way, dust control qualifies for the same scrutiny and protection as pavement or drainage—investments that create continuity instead of consumption.

Each of these practices starts small—a schedule, a log, a shared metric—but together they build a program that behaves like infrastructure. When the surface performs through a full season without constant intervention, the result isn’t just cleaner air or fewer complaints. It’s the quiet proof that a system once trapped in maintenance has learned to sustain itself.

The Ground That Holds Everything Else

In the end, the measure of good infrastructure isn’t how often it’s repaired, but how long it remains unremarkable. Roads, drains, and channels earn their worth in silence. Dust control belongs in that same category of work that disappears when it succeeds.

When surface stability becomes part of design rather than aftercare, the benefits extend far beyond the roadbed. Equipment lasts longer, workers breathe cleaner air, and communities spend fewer days wrapped in haze. Each outcome reinforces the next: safer visibility supports productivity, reduced water use conserves energy, and less material loss means less grading and waste. What begins as surface preservation unfolds as environmental and social continuity.

Thinking of dust control as infrastructure doesn’t diminish maintenance—it honors it. It recognizes that the people who keep the ground together are not just maintaining a surface; they’re maintaining the conditions that make every other investment possible. Stability, in this sense, is not an accident of upkeep but the result of design.

Because the most reliable systems are often the ones no one notices, and when the dust no longer rises, it means the foundation beneath everything else is finally holding steady.

To learn more about long-term dust control planning and the science that connects surface design, material performance, and environmental stewardship, explore our library of field insights and research.

Applications - Dust Control & Soil Stabilization Products

Leave a Reply